An Experiment in Reclaiming Reality and Reviving Solidarity

Big social change depends on big social movements, but our societies are too fragmented. That’s why——on the cliff-edge of climate collapse——it’s worth trying to rekindle trust and reclaim our collective ability to make sense of the world.

The Freedom Tour in Durham city center, North England. Photo by author.

What if we had such strong communities that people trusted one another more than they trusted what they read in the tabloids? What if all the attempts to separate us out into woke, white working class, migrants, scroungers, and so on could just be laughed off? What if we all actually knew each other?

These were the utopian dreamings behind the Freedom Tour across England and Wales this summer. The project didn’t finish building this at any meaningful scale. Utopia is still on the horizon. But it made it seem possible.

One of the central problems of all of our progressive mass mobilisations in the UK, from BLM, to XR, to Momentum, is that we cannot seem to persuade enough working-class and lower-middle-class communities that our demands for democracy and justice are demands for us all. Solidarity is in short supply because the media outlets that define our reality are not on our side. What on Earth can the mostly voluntary or understaffed campaign groups do against a billionaire-owned press pumping out cheap, sensational propaganda daily?

Well, we can disrupt it physically (as XR did by blocking Murdoch’s printing press), and we can start to build our own alternatives (in the UK we have Novara Media, Open Democracy or The Canary). But we also need to transcend its toxic world entirely. For us, this meant reviving the daunting practice of going out, meeting strangers, and trying to figure out how we arrived at such a lonely, fear-filled society—and what we can do to salvage a more beautiful, caring future.

For two months, a rolling crew of over twenty of us young activists took our big blue van into town squares and high streets across the country, walked up to strangers on the street, and said something along the lines of, “Hello, we’re a group of friends travelling the country. We think things are fucked and we’re trying to work out what to do about it. How are things going for you?”

Over 2,000 conversations later, the experience confirmed that listening and connecting with others is the absolute foundation for building a new kind of power beyond that of Murdoch, Rothermere and the Barclay Brothers. And we found that this is not as naively utopian as it seems. Newspaper stories and social media have a broad but thin power to define people’s understanding of the world. Real conversations with real breathing humans have the power to deeply change us all. This idea was the heart of the Freedom Tour.

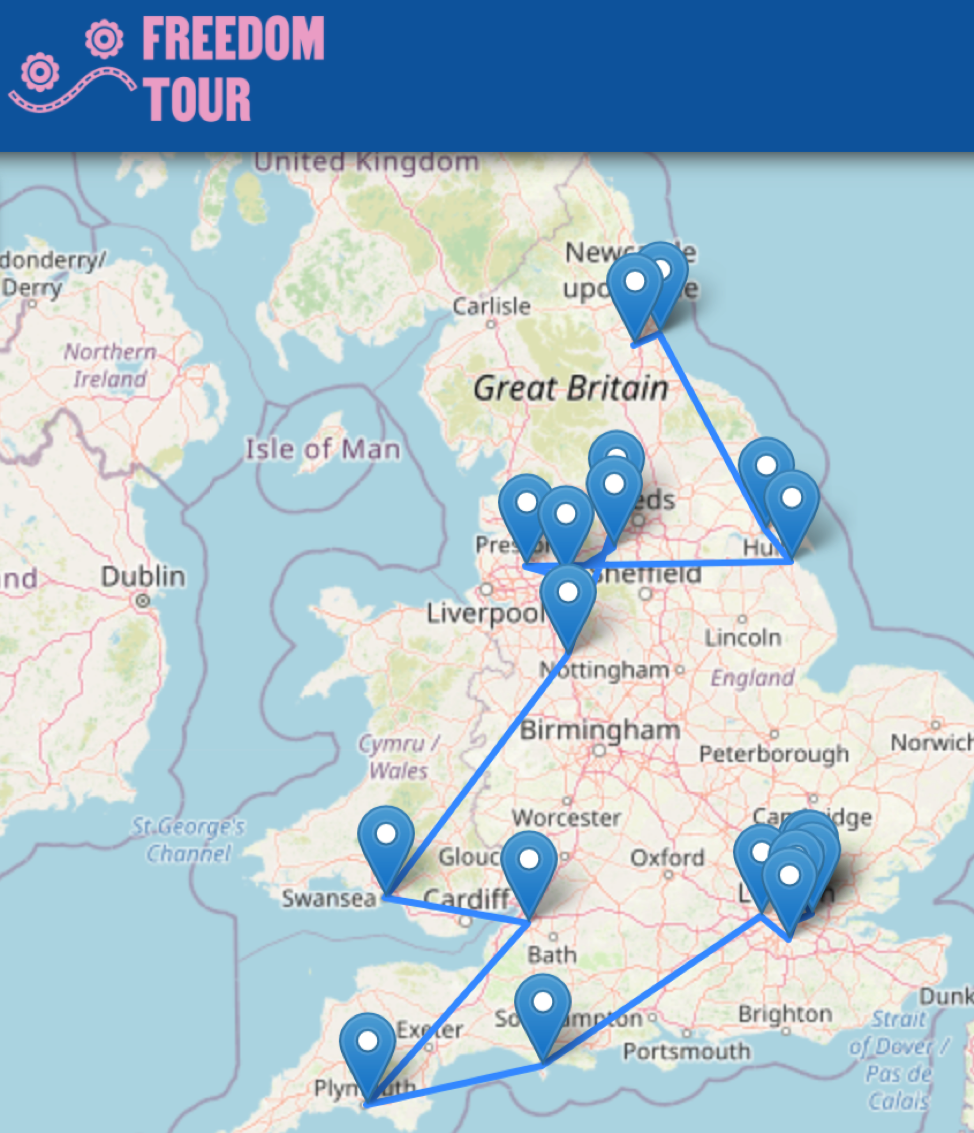

The route of the Freedom Tour.

Listening

The Tour was small and nimble. There were no more than 10 or 11 of us at any one time, all volunteering our time. We mostly knew each other from environmental campaigning and London squats. We started in County Durham, a region in the north east of England with a bitter, fresh history of working-class struggle in the defeat of the miners strike in the 1980s. Here, there’s a conspicuous absence of confidence in the Labour Party or any other channel for transformative politics (born out in the 2019 general election and more recently in the Labour Party losing control of the district council in 2021 for the first time in 100 years).

Nervous to avoid playing out the role of arrogant southerners or savouristic campaigners, we held curiosity as our animating principle. In practice, a homebrewed combination of Deep Canvassing (made famous by LGBT activists in Los Angeles in the 2010s) and Active Listening (from the North American clinical psychology tradition) helped us build trust quickly in our conversations with locals. This meant paying close attention, trying to summarise what we were hearing, and prioritizing the goal of making someone feel heard above the urge to convince them of something.

We found that when you ask people in the types of post-industrial, frequently neglected cities we went to how things are going, you’re typically met with either denial or apathy: things are either “Fine”, as in ‘Fine, I swear,’ or “Shit” as in, ‘Shit, and we all know it, so why are you even asking?’ Often older people were in denial, while the younger are aware but politically paralysed. When we did find someone older than 40 who was actively concerned about the state of the world, there was a 50/50 chance they were fretting about some variation of a vaccine, mask-wearing or lockdown racket.

Listen longer and this denial and apathy reveals pain and rage, different, but nonetheless present across age, race and education. We met countless young people in oppressive schools, enduring miserable treatment as queer and trans people. Many who have left school are stuck in meaningless jobs, worried they’ll be trapped in them for the rest of their lives. Most of them are fully aware of the unfolding climate and ecological catastrophe, but feel powerless to stop it.

As people get older, isolation becomes a dominant theme. Social anxiety and loneliness are leading many to seek comfort in toxic virtual communities. There’s a sense that something huge and unnamable has changed in their world, and they long to return to simpler, more communal times.

Listen for long enough and the differences that seemed startling to begin with start to shrink in front of a huge common ground opening up. We’re all a bit lonely, a bit fragile, struggling with the state of things, bewildered by change, worried about being judged; and we’re all absolutely, without fail, lacking any faith in our political and economic elites. We long for a world with more trust, more community, more connection and we each know that if we could just get together we could make it happen.

When this happens, everything seems possible. People, when properly heard, light up. They become more confident, feel less alone, and think carefully about their answers. We change too. From being backed-into-the-corner, weirdo, outcast activists, we come to feel part of a much bigger story of unfolding decline. And our sense of defeat, our powerlessness, our apathy melts away in front of such strong shared needs.

As our friend and writer) Indra Adnan of The Alternative UK points out in her new book, our dominant sensationalist media amplifies a story of self-defeat. We, the disenfranchised majority, buy into this story of our own powerlessness. “We are like the elephant,” she says “trained to stay tethered to a sapling tree long after it has the power to tear that tree from its roots”. Rediscovering each other through the fog of nasty stories and distrust, we can see clearly: a powerful mass movement is itching to be born.

Challenges

But listening and seamless connection is not always easy and it doesn’t always happen successfully. In a group discussion in Hull, two young women, and I and three older, white, working-class people try and fail to bridge some of the biggest divides in about half an hour. A few minutes into the chat and it’s soon clear that the older participants are all in on some secret. They’re referencing ‘nefarious hidden hands’ and ‘centuries-long orchestration’ and the rest of us are feeling baffled and left out. The label ‘conspiracy theorist’ is ringing around my head. I feel the need to show that I’m not one of them by expressing scepticism, but I don’t.

Then we start talking about BLM. They think it’s all a bit overblown. Some speculate that the BBC has cooked it up as a distraction. We listen for a moment, feel the pain of what they’re saying, then talk about our friends who are organising in BLM. One of the young women, a woman of colour, bravely shares her experience of structural racism. We go back and forth for a while. One older white woman eventually concedes that we’re probably right, that it’s worse than she first thought. The older men, though, clearly only want to hear from each other. The woman is doing the lion’s share of explaining the manifestations of racism, and although there’s some movement, it’s not much.

In this story, there’s no joyous reunion of people who are living in wildly different worlds. And the experience is a bit exhausting. The divisions are deep and we’ll need longer than half an hour to sort through them. But what our meeting did make possible was a jostling of settled categories. Our ‘conspiracy theorists’ turn out to be normally sceptical, passionate and simply longing for connection and understanding. Their ‘woke judgmental lefties’ turn out to be attentive, informed and capable of vulnerability. And although we didn’t come out glowing with the feeling you get when everyone agrees, there was more trust afterwards than there was before.

And trust, we’ve learned, is the bedrock for developing a new collective power. People can only believe in a world beyond the confines of the state and the market when they believe that people can coexist without coercion: we wouldn’t need bosses, prisons or profit incentives if we could rely on each other. At this moment in history, it is only a world beyond the market and an oligarchic state that will allow life’s continued existence. Rebuilding trust, then, becomes a matter of life and death. And because the market organizes social life around transactions, communities have been gutted of shared institutions, and the media barrages us with stories of division, it is at an all-time low. All of this applies to us, just as much as it did to the people we met. Beginning to connect with others reveals just how much we, too, need to learn to trust strangers.

The Freedom Tour holding a community conversation in Bradford. Photo by author.

What’s Next?

The shock of connection across these apparently insurmountable divides is fuel for something bigger. What if more of us did this? What if multiple groups of people did this at the same time? What if we stayed for longer in each place? What if what we learned could be shared, and we could build a mass movement with the voices and needs of everyone we’d met?

You can imagine what it might mean for this to happen in multiple towns and cities simultaneously. With more of us, we could target specific areas and be more thorough about who we meet. Over time, we would all build our own autonomous understanding of what’s going on in the country; we would have much more material for producing our own independent medias; and we would build a deeper culture of listening, attending to others' needs and collaborating across difference.

This tactic’s perceived naivety could be its strength. There’s nothing threatening about a bunch of people going out and listening. Why, then, couldn’t something like this be a formally accredited scheme for young people to participate in before starting university or a career? (The Sunrise movement’s Civilian Climate Corps proposal provides good inspiration). Supporting people to do this costs money—and there are surely are opportunity costs in advocating for political funds to be spent in any way—but there’s a lot to gain. At the very least we enrich the understanding that everyone has of the society they live in. At the most we create the conditions we need to radically transform our society, connect and activate all the latent power that is here, and shift from the extractivist, addicted, exploitative economy that’s killing us.

A key aspect of this was our lack of formal affiliation. No one trusts political parties. Many of us were returning to places we had canvassed for the 2019 Labour election, and the difference was palpable. Equally, if we had had a specific campaign goal, the whole listening exercise would have felt artificial. This presents a significant challenge: who do we say we are? If we’re part of a specific group, how do we be honest about our political attachments without alienating people? We erred on the side of caution—few logos, slogans or symbols; we opened by describing what we’re doing, rather than who we are; but we shared our experiences of groups and organisations we’d been part of, when it felt right to do so.

There’s a risk here of losing clarity over the group’s purpose and message. Being small and tight-knit, we kept clear on ours. But to do this at scale, we’ll need to invent some form of collective affiliation and organisation, while still steering clear of becoming overly polished, practiced and procedural.

New supporters helping decorate the van. Photo by author.

Part of this is rekindling a faith in solidarity, firing up our ability to imagine being with others. As author and activist Rob Hopkins reminds us, “Talk To Your Neighbour” was scrawled across Paris during the May 1968 uprisings. We cherish many of the slogans from this moment—it was one of our most recent opportunities to catalyse lasting systemic change. But of all the things to write on the walls then, this one has particular resonance.

The thing everyone remembers from that time is that everyone talked to each other more. As an English student in Paris described at the time: “those who had never dared say anything before suddenly felt their thoughts to be the most important thing in the world and said so. The helpless and isolated suddenly discovered that collective power lay in their hands. People just went up and talked to one another without a trace of self-consciousness.”

Maybe this kind of mass talking is an outcome of wider movements, or maybe it’s a cause. I suspect it is both, and if revolutionary change is some kind of vehicle, talking will be the fuel that moves it. In our time of fragile solidarity, how do we reverse engineer such a huge shift in social relations? We can weave that kind of open conviviality into our everyday lives, but the failure of COP suggests that now’s the time to organise at scale for hundreds of people to meet, connect and rediscover confidence in each other.

Greg Frey writes about democracy, social movements, resistance in the anthropocene, and humans doing more than we expect them to. You can find more of his work at openDemocracy, Novara Media and Minim.